Yet just before that, there was the Obeid culture, which is still poorly understood despite having initiated a fairly advanced urbanization that included irrigation, temples, and palaces, particularly in Eridu and Uruk, with a development of wealth, craftsmanship, and inequality, to the point that there seems to be no need to look for a superior people from elsewhere (let alone say where). This is confirmed by genetic analyses of burials in the region, which show a great diversity of origins, a melting pot of populations more or less distant from each other, rather than a new race that fell from the sky. We are therefore dealing with a mixture of all kinds of immigrants, of all colors, a colorful population combining all kinds of talents. The mystery of the language remains [This made me imagine that the Sumerian language, an isolated agglutinative language, very primitive at first, even phonetic and favoring vowels, could be a “pidgin,” an improvised immigrant language used to understand each other between different populations (including those from the Indus Valley) with very different languages—a gratuitous hypothesis, as I have no expertise in this area]. We should not idealize this original civilization too much, but it is a lesson that will be repeated throughout history: that the most powerful and progressive countries are the most open and mixed.

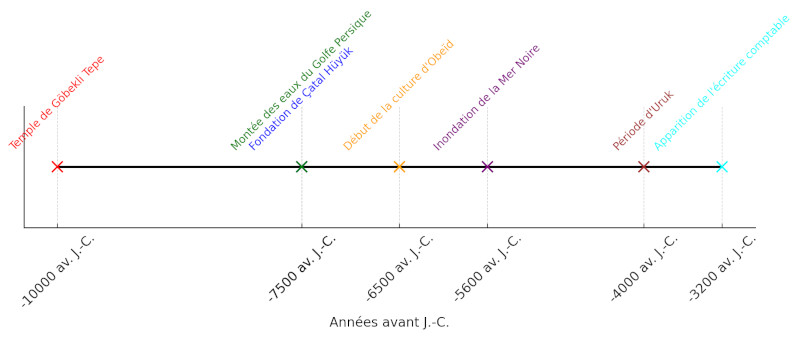

Remember that the first monumental temple we know of, at Göbekli Tepe in southern Turkey, dates from the end of the last ice age (Würm glaciation), around 10,000 BCE (the towers of Tell Qaramel and the surrounding dwellings are thought to be even older). There are already small underground houses, which we find again in the first villages. These temples were annual gathering places for semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers who consumed cereals and were even able to sow the best grains long before they settled down and switched to a new system of agricultural production. More than two millennia later, at Çatal Hüyük (also in Turkey), one of the oldest known cities, built around 7500 BC, consisted of small houses joined together, which were entered through the roof. Its inhabitants still lived largely from gathering and hunting before it came to house up to 8,000 people thanks to the increasing cultivation of domestic plants (wheat, oats). This transition to a less diverse diet, which did not provide enough vitamin D, resulted in skin bleaching, as would be the case much later for other European farmers, but made the Anatolians the first white sapiens, surrounded by black-skinned populations for several millennia (at least until the Indo-European invasions).

During this period of warming, the Persian Gulf, which was a vast fertile plain crossed by the Tigris and Euphrates rivers during the last glaciation, began to be flooded as the sea rose to its current level between 7500 and 6000 BC, This forced the Gulf populations connected to the Indus Valley to migrate northward to Eridu, becoming climate refugees. In addition, this rise in sea levels is thought to have caused the Bosphorus to break around 5600 BC, causing a sudden flooding of the Black Sea (the Great Flood?) which rose by 150 meters in just a few years. This disaster led to the displacement of agricultural populations that were quite dense along the shores of the Black Sea, creating a new wave of immigration to southern Mesopotamia, where the villages characteristic of the Ubaid culture gradually developed.

This was the setting for the Obeid period in Mesopotamia (6500-3750 BC), a time of multiple migrations of new populations, which began with the Holocene climatic optimum, bringing a humid climate to these former desert regions and encouraging the agricultural colonization of these lands, which had become marshy. However, just as important, around 5000-4000 BC, a new arid period began, prompting the development of more sophisticated irrigation techniques, whose efficiency led to a real population explosion. The management and maintenance of canals will make collective organization vital in this region, calling for centralized hierarchical power. Increased agricultural production and the growth of trade will also lead to the emergence of differentiated social classes (priests, artisans, farmers, local elites).

Urban centers could then have several thousand inhabitants, with temples, brick buildings, and paved roads. From the pivotal period of Uruk (4000-3100 BC), the city of Gilgamesh, which had a population of over 30,000, all the conditions were in place for the rise of the Sumerian city-states ruled by a deified priest-king. The legacy of Obeid was considerable, whether in irrigation, urban planning, or social and religious structures. Many craft techniques had been developed there previously (copper, ceramics) and intensive trade relations were maintained with distant regions. It was during this period that city walls and representations of battles appeared, with real armies replacing local militias. However, from 3100 BC, the city disappeared for more than a century, probably flooded, with tablets listing the kings before the flood followed by those who took up the torch after it.

While it is true that everything was already in place, what is nevertheless surprising about the subsequent rise of Sumerian civilization is that from that moment on, there was a considerable acceleration in technology, leading to gigantic works, with rigorous spatial organization for the maintenance of canals, the construction of ziggurats (stepped pyramids), thick walls, and immense palaces. The wealth of society, with its exaggerated hierarchy, actually preceded the development of accounting, which became necessary for trade, but whose widespread use subsequently gave a decisive new impetus to economic and historical development.

However, it seems that the economic and cultural dynamism of this early period of history (of writing) can be attributed at least in part to the incessant wars between cities that had become capable of financing armies—a competition that fostered innovation, as between the Greek cities later on, or closer to home, between the Italian cities of the Renaissance or in the European wars. Wars have always been accelerators of progress and seem to be an inevitable consequence of the (uneven) development of wealth and economic power, inevitably leading to empires (based on the law of the strongest).

Beyond this military pressure, the other lesson that can undoubtedly be drawn from the beginning of history, and which can be found in other progressive eras, is the characteristic of imperial capitals as cosmopolitan cities, cities of immigration, of “black heads” as the Sumerians called them, new Babylons each time. Athens, Alexandria, Rome, Baghdad, Constantinople, New York: all these megacities, hotbeds of creativity and progress, have been places of cultural mixing. And of course, despite the advantages it brings, cosmopolitanism has always been unpopular with locals and believers of all stripes, nostalgic for a unified, communal society, i.e., totalitarian and theocratic, which an empire bringing together multiple peoples and religions can no longer be. Technical power prevails over divine or community laws, which must bow to it. The dynamic of empire is that of globalization—accompanied this time by digital globalization—erasing local identities that have become folkloric.

It is just as interesting to note that each city was obliged to differentiate itself from its neighbors by its tutelary god (a kind of totem), even though their populations were not at all homogeneous, a pure convention of identity, belonging, and submission to the priest-king, not at all an expression of the soul of a people, their culture or their original beliefs but, as Lévi-Strauss showed, simply taking up neighboring myths or religions and inverting at least one term that stood for political opposition (narcissism of the small difference).

This shows that there is no essence or original identity; it is always the pressure of the environment (ecological, economic, technical, military, institutional) that determines us, determines our essence, our practices or beliefs, and guides evolution, which has become technical evolution as material power. We are not so much bound by blood ties and our past as by the challenges of our current situation, the imperatives of survival, and the preservation of the future. The past is over and will not return.

While the beginning of history (of writing) can be pinpointed very precisely to Uruk, this does not mean that Sumerian civilization was isolated. As we have seen, it brought together many Neolithic populations from the Black Sea to the Indus Valley, particularly the territories bordering the Persian Gulf, such as Elam (Susa), which was closely connected to Mesopotamia. Outside the Elamite country, further east, inland on the Iranian plateau, there was also the Jiroft civilization, which served as a trading center between Mesopotamia and the Indus. It is said that it may have corresponded to the mythical Aratta and that it could dispute the Sumerians' claim to the invention of writing (although this is doubtful and more likely to be a later development).

In any case, what is striking is the role of this region in the rise of civilizations, given that the Iranian plateau was already, admittedly a very long time before, the incubator of all humanity, which then spread out of Africa. Not only was it a necessary passageway to other continents, but a fairly small group, a few thousand Sapiens, is believed to have remained on this fertile plateau for more than 20,000 years, adapting to a colder climate before venturing into harsher latitudes. It was also during this period that there were a few interbreedings with Neanderthals, from whom all humans outside Africa inherited 2% of their genome. As this original population arrived 80-70,000 years ago before beginning to colonize the entire world 60-50,000 years ago, it is still too far back in time, but that does not prevent genetic traces from remaining today, which is surprising given that this geographical location has remained so important at various crucial moments in evolution.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-024-46161-7

https://www.futura-sciences.com/sciences/actualites/homme-on-sait-alle-homo-sapiens-apres-avoir-quitte-afrique-105515/

Another very recent genetic study (March 11, 2025) traces modern (narrative) language back to 135,000 years ago and to the Khoisan (or San) populations still present in South Africa but believed to have originated in the northeast, probably Ethiopia. This period coincides with an interglacial period lasting from 130,000 to 115,000 years ago, before the return of the Würm glaciation. The authors point out that symbolic behavior (such as funeral practices) only appeared in archaeological finds around 100,000 years ago, but it should be added that a visible decrease in testosterone in the chin was only observed from 80,000 years ago, which allowed for larger groups and therefore more complex cultures.

Finally, it is important to note the impact of the eruption of Mount Toba 73,000 years ago, which caused a further cooling of the climate. All of this leads us to the exodus from Africa to Iran, as we have seen, and then to the rest of the world with the warming 55,000 years ago. The mother tongue has been dated to 60,000 years ago using linguistic methods, and the Upper Paleolithic revolution occurred 50,000 years ago, which seems fairly consistent. We then had to wait until the end of the last ice age, which began between 30,000 and 13,000 years ago, to see the Neolithic period and the beginnings of civilization. When we talk about tens of thousands of years, it still seems quite fast and not as long ago as we might have thought.

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1503900/full

https://www.futura-sciences.com/sciences/actualites/homme-scientifiques-remontent-origines-langage-font-revelation-etonnante-120490/

We should add (things are moving very quickly) the catastrophic weakening of the Earth's magnetic field, the Laschamp event, which occurred between 42,200 and 41,500 years ago, dangerously increasing the sun's cancer-causing ultraviolet radiation. Our black and “red-skinned” ancestors are thought to have survived by covering themselves with red ochre, which protected them, while the white-skinned Neanderthals did not survive, which would have constituted a major bottleneck, including for Sapiens (which may also have eliminated the white-skinned Neanderthal/Sapiens hybrids?).

https://www.slate.fr/culture/creme-solaire-prehistorique-ancetre-homo-sapiens-uv-protection-ocre-vetement-neandertal-champ-magnetique

To top it all off, we should add the impact of the explosion of the Phlegraean Fields supervolcano (Italy) 39,000 years ago, which devastated the region and caused a volcanic winter lasting more than two years, but the demographic impact seems to have been fairly low.