Temps de lecture : 18 minutes Verifying the historical dialectic in our current reality (and the importance of being aware of it) does not mean allegiance to everything Hegel said about it during the Empire, nor does it mean adopting a conception of the mind that is no longer tenable in the age of generative artificial intelligence. Similarly, adopting Aristotelian logic cannot mean adopting his metaphysics or his justification of a patriarchal slave system. More generally, we must abandon the illusion that a philosopher has understood everything and that all we have to do is embrace his philosophy. Great philosophers are admired for the truths they discover or the questions they ask, which makes them indispensable to know, but the paradox is that these truths are always mobilized for a final denial (of death or suffering) and an idealization of reality, so that in (almost) all philosophies, the true is only a moment of the false. Philosophical demonstrations should not be taken seriously, with their implacable syllogisms that “bound the minds and did not reach things” (as Bacon insisted). Indeed, reality does not resist thought (fiction), only action. It is therefore more than legitimate to take up Plato's truths, like Aristotle, without accepting his theory of ideas or the immortality of the soul. Similarly, if it is no longer possible to be a Marxist-Leninist communist, this does not mean that one can no longer be a Marxist in the sense of being determined by the system of production and social relations, that is, by a materialist and dialectical conception of history determined by technical evolution. For Heidegger, it is even more caricatural because, of course, being touched by Being and Time or some of the themes it addresses cannot make one accept his Nazism and his pangermanist mysticism. Each time, powerful revelations that advance the argument are supposed to ultimately make us mistake bladders for lanterns and, in the name of their logical deductions, make us believe in our absolute freedom, in a God, in life after death, in a utopian end of history, or in an illusory bliss.

Verifying the historical dialectic in our current reality (and the importance of being aware of it) does not mean allegiance to everything Hegel said about it during the Empire, nor does it mean adopting a conception of the mind that is no longer tenable in the age of generative artificial intelligence. Similarly, adopting Aristotelian logic cannot mean adopting his metaphysics or his justification of a patriarchal slave system. More generally, we must abandon the illusion that a philosopher has understood everything and that all we have to do is embrace his philosophy. Great philosophers are admired for the truths they discover or the questions they ask, which makes them indispensable to know, but the paradox is that these truths are always mobilized for a final denial (of death or suffering) and an idealization of reality, so that in (almost) all philosophies, the true is only a moment of the false. Philosophical demonstrations should not be taken seriously, with their implacable syllogisms that “bound the minds and did not reach things” (as Bacon insisted). Indeed, reality does not resist thought (fiction), only action. It is therefore more than legitimate to take up Plato's truths, like Aristotle, without accepting his theory of ideas or the immortality of the soul. Similarly, if it is no longer possible to be a Marxist-Leninist communist, this does not mean that one can no longer be a Marxist in the sense of being determined by the system of production and social relations, that is, by a materialist and dialectical conception of history determined by technical evolution. For Heidegger, it is even more caricatural because, of course, being touched by Being and Time or some of the themes it addresses cannot make one accept his Nazism and his pangermanist mysticism. Each time, powerful revelations that advance the argument are supposed to ultimately make us mistake bladders for lanterns and, in the name of their logical deductions, make us believe in our absolute freedom, in a God, in life after death, in a utopian end of history, or in an illusory bliss.

So, let us repeat that what should make us adopt Hegelian dialectics is its verification in concrete terms and in the particularity of phenomena, both in logic and in history (political, moral, aesthetic), a dialectic that we undergo and cannot ignore. However, this should not blind us to the totality of the system—and in particular to the Phenomenology—and cause us to lose all critical spirit. It is even essential to deconstruct the system based on the confusion between individual consciousness and the historical spirit. As has been pointed out, it was precisely the decision to begin with consciousness that gave impetus and coherence to the writing of the Phenomenology, approaching truth and spirit as subjects rather than from an external point of view. This confusion between individual consciousness and the history of the Spirit is, however, untenable, even though the role of the individual is minimized, particularly in view of the “tricks of reason.” The dialectic of consciousness that unfolds there could be attributed at most to a kind of transcendental consciousness, to the spirit of the times (too quickly identified by Kojève as Man) or, better, to logical constraints but not to the activity of the individual, as the last paragraph of the preface makes clear. It is all the more surprising that the Introduction claims to be a science of the experience of consciousness. In his lecture on Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit (1931), Heidegger has no trouble criticizing, in the name of phenomenological intentionality and its noesis, the reconstruction of consciousness from its perceptions, when in fact there is always a prior understanding of the totality, of the meaning of the situation. Consciousness never begins from the immediate; it is always already there, in a situation, embedded in a history, social relations, discourses, always already consciousness for the Other and language, from the beginning and not only at the end of the journey. As Lev Vygotsky showed, child development does not proceed from the individual to the social, but rather from social discourse to the individual.

In the Philosophy of Mind of his Realphilosophie, just preceding Phenomenology, Hegel admitted this and that there is no realization of self-consciousness except in the people (the collective), yet what is appealing in his Phenomenology is that he turns it into a novel in which consciousness is supposed to be constructed in its own experience. This is again what he presents in Chapter IV, “The Truth of Self-Certainty,” where consciousness achieves socialization through “self-consciousness in and for itself when and because it is in and for itself for another self-consciousness” (p. 155), that is, “an I that is a We, and a We that is an I.” (p. 154). The first part, entitled “Independence and Dependence of Self-Consciousness,” introduces the dialectic of Master and Slave, which is the best-known part of the work but the subject of much misunderstanding. Kojève makes it the pivot of his questionable Hegelian-Marxist-Heideggerian interpretation, combining struggle and labor with the anxiety of death, but this dialectic, which has nothing historical about it, must be reduced to its fictional and parabolic nature (a subject devoid of any other characteristic than mortality and a dialectic arising from its natural (bestial) basis and its negation in law).

Lire la suite

Returning to the history of religions convinced me of the inadequacy of theories of religion, whether those of Aristotle, Hegel, or Durkheim, i.e., those based on individual subjectivity or on their social function. It is not possible, in fact, to remain at this level of generality and base these historical productions on the psychological structures of the species, nor to remain at this sociological functionalism (Durkheim) or at the representation of the truth of a people (Hegel), given their link to material conditions (hunter-gatherers, farmers, city-states, empires).

Returning to the history of religions convinced me of the inadequacy of theories of religion, whether those of Aristotle, Hegel, or Durkheim, i.e., those based on individual subjectivity or on their social function. It is not possible, in fact, to remain at this level of generality and base these historical productions on the psychological structures of the species, nor to remain at this sociological functionalism (Durkheim) or at the representation of the truth of a people (Hegel), given their link to material conditions (hunter-gatherers, farmers, city-states, empires).

We must recognize the historical nature of the ideologies that structure us but belong entirely to their time, in the sense that they very quickly become outdated in subsequent periods. It is good to spell out the obvious truths that we acted on without thinking at the time, and there is no one better than Kojève to formulate the implacable logic behind them, the falsity of which we can now fully appreciate. It is useful to quote some excerpts to show how convincing they seem at first glance. Here, Kojève rigorously exposes the entire revolutionary mythology of the Stalinist era, which seems so appalling to us today. Once again, we see an illustration of an excess of logic unrelated to the facts, of an idealism that ignores reality despite its professed materialism—something that, nevertheless, we may have naively shared.

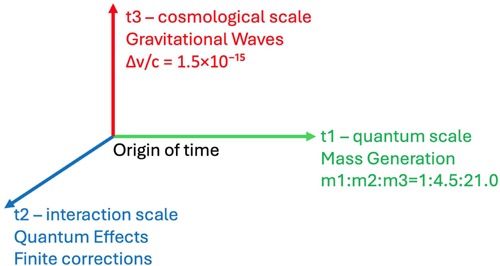

We must recognize the historical nature of the ideologies that structure us but belong entirely to their time, in the sense that they very quickly become outdated in subsequent periods. It is good to spell out the obvious truths that we acted on without thinking at the time, and there is no one better than Kojève to formulate the implacable logic behind them, the falsity of which we can now fully appreciate. It is useful to quote some excerpts to show how convincing they seem at first glance. Here, Kojève rigorously exposes the entire revolutionary mythology of the Stalinist era, which seems so appalling to us today. Once again, we see an illustration of an excess of logic unrelated to the facts, of an idealism that ignores reality despite its professed materialism—something that, nevertheless, we may have naively shared. It is bold to speak of new physical theories; there are far too many that we will never hear about again, and one must admit that the January paper “Three‑Dimensional Time: A Mathematical Framework for Fundamental Physics” seems a little too audacious. It not only postulates three dimensions of time—which is already hard to swallow—but also that the three spatial dimensions and even particles themselves are produced by the interaction of these three differentiated forms of physical temporality. This idea is not entirely new, since there were already reasons to think that the time parameter t should have

It is bold to speak of new physical theories; there are far too many that we will never hear about again, and one must admit that the January paper “Three‑Dimensional Time: A Mathematical Framework for Fundamental Physics” seems a little too audacious. It not only postulates three dimensions of time—which is already hard to swallow—but also that the three spatial dimensions and even particles themselves are produced by the interaction of these three differentiated forms of physical temporality. This idea is not entirely new, since there were already reasons to think that the time parameter t should have  It is current events in their most dramatic form that confront us with dialectical reversals that history and Hegelian philosophy can illuminate. We have seen that Hegel's first concern in separating himself from Schelling was to avoid abstraction by trying to stick to concrete phenomena and follow their dialectical movements in their diversity, without therefore needing to define this dialectic in advance (which he will do at the end of the Logic). It is not primarily a formal, preconceived method. Despite everything, his opposition to Schelling implies a rejection of immediacy as well as of a static dialectic between opposites, in equilibrium (philosophy of identity). The most general definition of dialectics for Hegel is therefore its dynamic, evolving, productive, transformative nature. As in Fichte, every action provokes a reaction, every intention (freedom) encounters resistance (external world), requiring an effort and testing its limits, but each time forming a new totality where each position in its one-sidedness collides with the opposition of the other until it has to integrate this otherness into their reciprocal recognition, resulting from the conflict. "It is only this equality reconstituting itself or the reflection in oneself in the being-other that is true - and not an original unity or an immediate unity as such". (Phenomenology, tI p17-18)

It is current events in their most dramatic form that confront us with dialectical reversals that history and Hegelian philosophy can illuminate. We have seen that Hegel's first concern in separating himself from Schelling was to avoid abstraction by trying to stick to concrete phenomena and follow their dialectical movements in their diversity, without therefore needing to define this dialectic in advance (which he will do at the end of the Logic). It is not primarily a formal, preconceived method. Despite everything, his opposition to Schelling implies a rejection of immediacy as well as of a static dialectic between opposites, in equilibrium (philosophy of identity). The most general definition of dialectics for Hegel is therefore its dynamic, evolving, productive, transformative nature. As in Fichte, every action provokes a reaction, every intention (freedom) encounters resistance (external world), requiring an effort and testing its limits, but each time forming a new totality where each position in its one-sidedness collides with the opposition of the other until it has to integrate this otherness into their reciprocal recognition, resulting from the conflict. "It is only this equality reconstituting itself or the reflection in oneself in the being-other that is true - and not an original unity or an immediate unity as such". (Phenomenology, tI p17-18) The 2002 text, “

The 2002 text, “

Verifying the historical dialectic in our current reality (and the importance of being aware of it) does not mean allegiance to everything Hegel said about it during the Empire, nor does it mean adopting a conception of the mind that is no longer tenable in the age of generative artificial intelligence. Similarly, adopting Aristotelian logic cannot mean adopting his metaphysics or his justification of a patriarchal slave system. More generally, we must abandon the illusion that a philosopher has understood everything and that all we have to do is embrace his philosophy. Great philosophers are admired for the truths they discover or the questions they ask, which makes them indispensable to know, but the paradox is that these truths are always mobilized for a final denial (of death or suffering) and an idealization of reality, so that in (almost) all philosophies, the true is only a moment of the false. Philosophical demonstrations should not be taken seriously, with their implacable syllogisms that “bound the minds and did not reach things” (as

Verifying the historical dialectic in our current reality (and the importance of being aware of it) does not mean allegiance to everything Hegel said about it during the Empire, nor does it mean adopting a conception of the mind that is no longer tenable in the age of generative artificial intelligence. Similarly, adopting Aristotelian logic cannot mean adopting his metaphysics or his justification of a patriarchal slave system. More generally, we must abandon the illusion that a philosopher has understood everything and that all we have to do is embrace his philosophy. Great philosophers are admired for the truths they discover or the questions they ask, which makes them indispensable to know, but the paradox is that these truths are always mobilized for a final denial (of death or suffering) and an idealization of reality, so that in (almost) all philosophies, the true is only a moment of the false. Philosophical demonstrations should not be taken seriously, with their implacable syllogisms that “bound the minds and did not reach things” (as  Over the long term, the only indisputable and cumulative progress is that of knowledge (of techno-science). Of course, this does not mean that everyone has access to it, nor that there will not be setbacks, knowledge that is forgotten or suppressed in the short term before being rediscovered. However, despite what some may claim, this objective progress is largely independent of us, imposed by experience that most of the time contradicts our beliefs. Far from achieving absolute knowledge, however, this accumulation of knowledge reveals new unknown territories each time, so much so that we can say that ignorance grows as our knowledge destroys our old certainties and prejudices.

Over the long term, the only indisputable and cumulative progress is that of knowledge (of techno-science). Of course, this does not mean that everyone has access to it, nor that there will not be setbacks, knowledge that is forgotten or suppressed in the short term before being rediscovered. However, despite what some may claim, this objective progress is largely independent of us, imposed by experience that most of the time contradicts our beliefs. Far from achieving absolute knowledge, however, this accumulation of knowledge reveals new unknown territories each time, so much so that we can say that ignorance grows as our knowledge destroys our old certainties and prejudices. It's all a question of tempo, but it is very difficult to accurately assess the temporality of each process because there are several whose multiple combinations cannot be predicted. Modern physics has refuted Newton's concept of absolute time, which nevertheless remains the a priori form of our sensibility, as Kant said. We constantly think as if time were linear, when in fact there are many different temporalities intersecting in a present that has nothing of the consistency of an instantaneous slice of life or the immobile coexistence of all beings that mystics portray. There is only a multiplicity of trajectories with their own times, some cyclical or very short-term, others astronomical. It is therefore certain that we are mortal and that our planet is not eternal either, nor is our sun, nor even the entire universe, which is doomed to disappear (before its rebound?). However, it is very difficult for us to imagine the billions of years that were necessary for life to become so complex.

It's all a question of tempo, but it is very difficult to accurately assess the temporality of each process because there are several whose multiple combinations cannot be predicted. Modern physics has refuted Newton's concept of absolute time, which nevertheless remains the a priori form of our sensibility, as Kant said. We constantly think as if time were linear, when in fact there are many different temporalities intersecting in a present that has nothing of the consistency of an instantaneous slice of life or the immobile coexistence of all beings that mystics portray. There is only a multiplicity of trajectories with their own times, some cyclical or very short-term, others astronomical. It is therefore certain that we are mortal and that our planet is not eternal either, nor is our sun, nor even the entire universe, which is doomed to disappear (before its rebound?). However, it is very difficult for us to imagine the billions of years that were necessary for life to become so complex. A small number of fundamental concepts that run counter to religious, metaphysical, or ideological ways of thinking are enough to overturn the usual idealistic and subjectivist understanding of our humanity (and politics). The concepts examined here (information, narrative, after-the-fact, exteriority) are all well known and verifiable by everyone, and there would be no mystery or difficulty if materialist (ecological) conceptions were not so vexing and did not conflict with our narratives, which is why they are constantly denied or repressed in order to preserve the fictions of unity that keep us alive. We will see, moreover, that these fundamental concepts touch on the most sensitive debates of our time (digital technology, democracy, identity, racism, sociology, etc.).

A small number of fundamental concepts that run counter to religious, metaphysical, or ideological ways of thinking are enough to overturn the usual idealistic and subjectivist understanding of our humanity (and politics). The concepts examined here (information, narrative, after-the-fact, exteriority) are all well known and verifiable by everyone, and there would be no mystery or difficulty if materialist (ecological) conceptions were not so vexing and did not conflict with our narratives, which is why they are constantly denied or repressed in order to preserve the fictions of unity that keep us alive. We will see, moreover, that these fundamental concepts touch on the most sensitive debates of our time (digital technology, democracy, identity, racism, sociology, etc.). Following on from

Following on from  Objectively speaking, what should concern us most is the risk of ecological collapse and preserving our living conditions and natural resources. However, we must not confuse one collapse with another, as this only encourages confusion. It is not enough to engage in a contest of exaggerations on the pretext that a collapse is inevitable! Prophecies of the end of the world at noon next year are old news.

Objectively speaking, what should concern us most is the risk of ecological collapse and preserving our living conditions and natural resources. However, we must not confuse one collapse with another, as this only encourages confusion. It is not enough to engage in a contest of exaggerations on the pretext that a collapse is inevitable! Prophecies of the end of the world at noon next year are old news. We have to admit that our world has changed radically in recent years, with the advent of the internet and then mobile phones, but we haven't seen anything yet, and with the arrival of artificial intelligence, nothing will ever be the same again, despite all the resistance to change that is destroying the old order.

We have to admit that our world has changed radically in recent years, with the advent of the internet and then mobile phones, but we haven't seen anything yet, and with the arrival of artificial intelligence, nothing will ever be the same again, despite all the resistance to change that is destroying the old order. It seemed worthwhile to attempt a brief summary of human history from a materialistic point of view, focusing not so much on the emergence of man as on what shaped him through external pressures and led us to where we are today, where the reign of the mind remains that of information and therefore of externality. Sticking to the broad outlines is certainly too simplistic, but it is still better than the even more simplistic mythical accounts that we tell ourselves. Moreover, it shows how we can draw on everything we don't know to refute idealistic beliefs as well as ideological constructs such as Engels' “The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State,” which have no connection with reality.

It seemed worthwhile to attempt a brief summary of human history from a materialistic point of view, focusing not so much on the emergence of man as on what shaped him through external pressures and led us to where we are today, where the reign of the mind remains that of information and therefore of externality. Sticking to the broad outlines is certainly too simplistic, but it is still better than the even more simplistic mythical accounts that we tell ourselves. Moreover, it shows how we can draw on everything we don't know to refute idealistic beliefs as well as ideological constructs such as Engels' “The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State,” which have no connection with reality.

As globalization progresses, more and more people would like to escape it by returning to an idealized nation in splendid isolation, even though the slightest attempt at originality raises storms and forces a return to the past. External pressure is undeniably homogenizing, just as prices tend to converge in open markets. Lamenting or rejecting this fact does not change anything, except to build a wall between us and the rest of the world, which is no longer tenable. We are part of this world and this time, just like this weak Europe. The only territory we have left is that of proximity, which is not insignificant and is the place for local alternatives to commercial globalisation, but it will not prevent the world from continuing to unify.

As globalization progresses, more and more people would like to escape it by returning to an idealized nation in splendid isolation, even though the slightest attempt at originality raises storms and forces a return to the past. External pressure is undeniably homogenizing, just as prices tend to converge in open markets. Lamenting or rejecting this fact does not change anything, except to build a wall between us and the rest of the world, which is no longer tenable. We are part of this world and this time, just like this weak Europe. The only territory we have left is that of proximity, which is not insignificant and is the place for local alternatives to commercial globalisation, but it will not prevent the world from continuing to unify. It seems that philosophy has remained stuck on the question of language, unable to integrate the concept of information except to offer a superficial critique of its triviality. This is all the more unfortunate given that it is therefore incapable of thinking about our current reality, which is precisely that of the information age. However, this article is not about current events, news reports, communication, or networks, but rather about considerations that may seem much more outdated regarding the very concept of information as it has manifested itself in the digital and computerized world. Both science and lifestyles have been profoundly affected by this, without philosophers seeming to be particularly concerned, except for vain and completely useless moral condemnations, when it is their categories that should be shaken up.

It seems that philosophy has remained stuck on the question of language, unable to integrate the concept of information except to offer a superficial critique of its triviality. This is all the more unfortunate given that it is therefore incapable of thinking about our current reality, which is precisely that of the information age. However, this article is not about current events, news reports, communication, or networks, but rather about considerations that may seem much more outdated regarding the very concept of information as it has manifested itself in the digital and computerized world. Both science and lifestyles have been profoundly affected by this, without philosophers seeming to be particularly concerned, except for vain and completely useless moral condemnations, when it is their categories that should be shaken up. Following on from my

Following on from my